Unlearning Empire, Re-Membering Earth

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

– Mary Oliver, Wild Geese

Sitting in the garden here in Cupar, drinking in this late September warmth, a familiar sound draws my gaze to the flight path above – not of aeroplanes, but wild geese wending their way south for winter. I love their dynamically shifting V-formations, supporting each other in their long journey home. The way they listen to the wind with their wings, following the flow that guides them on their way, makes my heart sing.

I’m also inspired to remember that the ancient ancestors of these beautiful geese also faced extinction. Rather than disappearing as we once thought, we now know that some of the dinosaurs found their wings. They adapted to changing conditions, discovering hidden depths of capacity within themselves.

In these times, there is little doubt that once again the Earth is calling on us all to evolve – to find new forms for living together. And we can see this isn’t easy. Change seems to bring fear and resistance. That is to be expected.

The secret of flight seems to lie in becoming empty. Even the bones of birds are hollow, giving them lift.

~ ~ ~

We might see ourselves as children of empire, either rebelling against or obedient to (two sides of the same coin) a belief that a particular way of living is advanced, superior, and unquestionably right. We might see how this pattern becomes embodied in our movements, our emotional responses, and our ways of thinking. And yet, somehow its grasp is never complete.

For before, during, and after empire, here is the Earth. We are first and foremost of the Earth and anything we have learned from empire, we can unlearn. Not simply with our intellect but with our whole being. In unlearning, we allow ourselves to evolve. Not by force, not by strategy, not by grandeur, but through gentleness, simplicity, and community.

This transformation of our culture is so critical, it can’t be rushed. Instead, we might honour the value and power of gentleness, of slowing down and of allowing ourselves to be transformed from within by the power of life itself. This inner transformation seems to be essential to the outer cultural shift we are all desperately hoping for.

The wing muscles of the wild geese are strong, it’s true. But it’s the sensitivity of the feathers that lets them follow the wind. It’s the humility of their hearts that allows them to take turns leading. No one is in front in order to impress the others, but to support them just as that one has been supported by the others.

Disconnection is both the root and the fruit of empire. There can be no hierarchy without separation, no ‘other’ to conquer and control. For anyone to draw lines on a map or between kinds of people, effectively declaring some lives are more important than others relies on the imagination that Life is fragmented, that the Earth is not a singular being. Of course, we each have our own wonderful and distinctive way of being in the world. Life is beautifully diverse. And it is all deeply connected.

When viewed through the lens of empire, life seems to be distorted. Even the teachings of the nice young man 2,000 years ago who said simply “love each other” somehow became justification for Crusades and sectarian violence when translated through the world-view of the Roman Empire. If we wish to transform our world, we cannot do so without unlearning the embodied and psychic habit of separating ‘us’ and ‘them’ or ‘me’ from the ‘world’.

We might now choose to replace the word empire with trauma and see how it still makes sense. Empire seems abstract, maybe distant. Trauma is intimate and embodied. But the patterns are the same. Empire is both cause and result of intergenerational trauma. My Oglala Lakota relative* Edwina Brown Bull of Pine Ridge Reservation speaks powerfully of this when she talks of the history of boarding schools for indigenous people as part of the genocidal policies of the US (and Canadian) governments which we are hearing about now in the news.

* Edwina calls me her relative and I call her mine because in the Lakota philosophy Mitákuye Oyás'iŋ (All Are Related). She and I are working together as part of a wider team at Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota with the Heart Of Living Yoga Foundation to share heart-centred yoga and meditation practices for the healing of Native Nations.

“They can only do to us what was already done to them.”

“It’s important to understand that Federal Indian Policy played a major role in not only dismantling who we were as a people, but the land and the boarding schools were all a part of the Federal Indian Policy that were an attempt to assimilate the indigenous people to be … [weighted pause] emotion just struck me … it was an attempt for us to be something that they wanted us to be. […] As I’m learning more about the Federal Indian Policy and the impact it had on everything – every part of our indigenous nations – the one thing I have to remind myself is that they can only do to us what was already done to them. So when I say that statement, I’m looking at it not from a victim standpoint but more from a place of seeing that there was trauma within them in order for those to acts to happen to us. [There was trauma at] all levels from governmental to personal – all those levels!”

I love her deep sense of compassion, of recognising the suffering of those she might be tempted to call an enemy. But she does not. She sees only human beings, being human. And she knows that compassion is key to all healing, all beneficial change. Including, perhaps especially, compassion for ourselves. Notice how she saw that emotion struck her while she spoke and how she embraced it with compassion before continuing. Decolonisation, we might say, is a profound process of recovery from trauma and a re-opening to the fullness, wholeness, and beauty of life.

A parallel trauma still exists within the elite of Scottish (and British) society where young children are separated from families and sent to boarding school. Here they are not encouraged to be who they are … but to be something that others want them to be. For empire to continue, domination must be taught. And for it to end, it must be unlearned – not just intellectually, but in our whole being. Having worked both collaboratively and therapeutically with individuals sent to such schools, I can say the effect of the trauma is palpable. And yet, there is also great beauty and resilience. I have learned so much from boarding school survivors in Scotland and among the Lakota.

Edwina’s insights also tie in with recent scientific research which shows the biochemical signs of trauma exist equally within those we might call perpetrators and those we might call victims. Everyone is tangled up together in the same mess and we can only come untangled together. This is not to disregard the benefits of privilege by any means, but rather to recognise that material and social privilege is not the same as emotional wellbeing and a healthy sense of place in the world.

We all handle trauma differently. Many of us learn to survive by thinking to ourselves “it wasn’t that bad” and focussing our attention on what we might think of as “bigger problems”. Others get very caught up in the trauma, holding it close and making it an identity. We might say we have nothing to lose but our chains, but what if our chains are how we make sense of the world?

When we look closely at these big questions – like decolonisation, degrowth, and decarbonisation (i.e. transforming the foundation of our whole way of life), we might see that they are made up of a whole lot of smaller questions about our every day lives. It’s not logical to say we can have a healthy, sustainable, and equitable culture in Scotland without nurturing the conditions which allow the healing of the traumas that keep us feeling disconnected in various ways. That would be a bit like trying to help an ecosystem recover without tenderly nurturing the plants and animals…

~ ~ ~

Many of the great spiritual traditions teach that to heal the wounds we carry with us and to be of greater service to humanity and our whole planet, we might choose the path of becoming empty, like wild geese. In the Oglala Lakota tradition, we see very clearly how this supports a non-capitalist way of life:

We are called to become hollow bones for our people and anyone else we can help, and we are not supposed to seek power for our personal use and honor. What we bones really become is the pipeline that connects Wakan-Tanka, the Helpers and the community together. This tells us the direction our curing and healing work must follow and establishes the kind of life we must lead. It also keeps us working at things that do not bring us much income. So we have to be strong and committed to stick with this, otherwise we will get very little spiritual power, and we will probably give up the curing and healing work.

Frank Fools Crow, Oglala Lakota Holy Man

Here Fools Crow describes a radical openness to life and to Spirit – to listening to what is guiding us to serve others rather than become focussed on our selves.

In the Christian tradition, becoming ‘hollow bones’ is called kenosis (self-emptying). Rather than seeing Jesus as an authority to be obeyed (Roman Empire translation), we might see him as a great wisdom teacher who demonstrated a mystical path of becoming empty much as Lakota, Buddhist, Yoga, and other traditions teach. When we see the word mystical, we might think it’s something airy-fairy, but this work is profoundly practical for healing the patterns of empire/trauma within and around us. Cynthia Bourgeault describes a simple three-step process inspired by his teachings sometimes called ‘The Welcoming Prayer’. First we simply observe any sensation in our body which is tight, or holding, in any way. Common areas include bottom, belly, shoulders, and jaw. Maybe you notice some areas holding now? Perhaps our usual way of operating is to try to banish anything we don’t like from our experience or just grit our teeth and bear it. This practice offers another way. Instead, we start by simply “acknowledging what is going on internally during a distressing physical or emotional situation, ‘welcoming’ it, and letting it go” (The Wisdom Jesus p172, original emphasis). In other words, letting the soft animal of your body relax and embrace being present in this living moment.

My teacher’s teacher in Yoga, Swami Satchidananda, also advocated a kind of kenosis which he called Undoism.

People often ask me, “What religion are you? You talk about the Bible, Koran, Torah. Are you a Hindu?” I say, “I am not a Catholic, a Buddhist, or a Hindu, but an Undo. My religion is Undoism. We have done enough damage. We have to stop doing any more and simply undo the damage we have already done.”

Unlearning empire, unlearning separation, unlearning identifying with categories that keep us apart … undoing the damage we have done and recognising ourselves as integral with Nature, with Life Itself. Through the practices of Yoga (including breathing, meditation, postures, awareness of the mental patterns, community and devotion to something which is greater than ourselves) or similar paths of healing and transformation, we find our sense of separation becoming thinner as we come undone.

In undoing or emptying, we discover a fullness, a great beauty and sense of wonderment, much as ‘degrowth’ invites us to grow in ways that aren’t just about money but are about the wholeness of life. Until we empty ourselves of our need for more, we’ll never discover the richness that we already are. Capitalism depends very much on the suppression of our connection with life, with our bodies, with our pain, and with our healing. We’re invited, instead, to distract ourselves endlessly with either working or consuming. Simply being, breathing, enjoying what life brings to us and those around us, gently undermines the structures of empire/trauma that hold us frozen in a pattern that can only lead to collapse. Instead of that road, we might instead choose the radical self-care that enables us to remember that our place here on Earth is valuable, our unique contributions needed, and our healing that is the foundation of all of that.

Through emptying, we find our inner world becoming quieter and more peaceful. It is only when we are quiet inside that we might really listen. We can listen to each other in a way that allows for real community, real healing, real transformation. We can listen to that quiet inner voice of intuitive conscience that guides us to the most helpful words and deeds. We might even find we can listen to the earth, to the trees, to other beings in ways our culture tells us is impossible. For indigenous cultures, however, it is perfectly natural to listen to the trees.

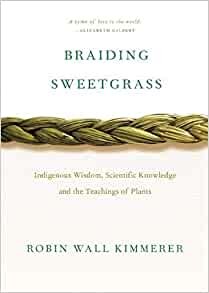

I too was a stranger at first in this dark dripping forest perched at the edge of the sea, but I sought out an elder, my Sitka Spruce grandmother with a lap wide enough for many grandchildren. I introduced myself, told her my name and why I had come. I offered her tobacco from my pouch and asked if I might visit in her community for a time. She asked me to sit down, and there was a place right between her roots. (Robin Kimmerer Wall, Braiding Sweetgrass p206)

Meanwhile, modern science is only just beginning to see how much the trees speak to each other. As we all evolved together, made of the same stuff, is it so hard to imagine that we might also listen to the trees and they to us? If we wish to develop a sustainable way of life, listening to the teachings of indigenous people (including the folk wisdom and old tales of our own indigenous ancestors here in Scotland) and finding our own direct connection with the land around us is invaluable.

Through individual and collective practices of healing, our relationships are transformed: with ourselves, each other, the land, and whatever word we might like to use for the Infinite. The great anarchist Gustav Landauer pointed to this as the essence of revolution, for no institution is a transcendental being, above and beyond every day life. “The state”, he wrote, “is a social relationship; a certain way of people relating to one another. It can be destroyed by creating new social relationships; i.e., by people relating to one another differently.” Following indigenous teachings and great eco-mystics like Mary Oliver, Kathleen Jamie, Nan Shepard, and John Muir, we might expand this to include our relationships with trees and mountains, with earthworms and songbirds, with healing herbs and clear running waters.

We might look to the inspiring radical herbal health project known as Grass Roots Remedies. They are a workers’ cooperative, inspired by Permaculture principles, who are organically growing, harvesting, preparing, and distributing herbal medicine through public outreach projects, online sales, shops, and at their low-cost herbal clinics in Wester Hailes and Granton. The team focus on plants that grow wild in Scotland, rather than importing herbs which may be endangered by over-harvesting, and teach self-care through earth connection, just as indigenous cultures (including in Scotland) have always done.

We are also blessed in Scotland to host a number of forest gardens, which demonstrate a very different relationship with land than we see in most domesticated home gardens or in industrial agriculture. Some are inspired by permaculture principals – including Graham Bell and Nancy Woodhead’s ‘Garden Cottage’ in Coldstream, Euan Sutherland’s ‘Rowan Refuge’ in Glasgow, or Alan Carter’s forest garden allotment in Aberdeen. Meanwhile, Rosa Steppanova and James MacKenzie’s ‘impossible garden’ in Shetland is inspired by her memories of growing up in the Black Forest and their shared passion for wildlife, beauty, and ecological diversity. Back in the Borders, Bird Gardens Scotland is reforesting and hosting programmes for conservation breeding of rare species of wild and domesticated birds. These gardens produce tremendous yields not only in terms of foodstuffs (Graham and Nancy regularly harvest 1.25 tons of food in a year on a fifth of an acre) but in space for wildlife to thrive and for human visitors to be inspired by what is possible with care, planning, and a love of nature.

If we wish to continue the thread of this essay in taking inspiration from indigenous cultures, we might look also to the Landback movement in North America and elsewhere to return land to indigenous stewardship and collective liberation. While the Scottish government’s support for community buyouts is laudable, we might like to set our sights on deeper transformation as we collectively consider the opportunities provided by Scottish independence. We might ask, what could Landback look like here?

Maybe we don’t need to know what the future holds, but simply to focus on deepening our connection with the Earth, with Life, and supporting each other to find our wings. Let’s see how we fly!

References

Fools Crow: Wisdom and Power by Thomas Mails is the source of the quote from Fools Crow above.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Kuhn, Gabriel (2010) Gustav Landaur: Revolution and Other Writings. London: PM Press.

Healing Collective Trauma by Thomas Hubl makes clear the connection between trauma and oppressive social structures — and how we can all participate in the healing.

Finding the Mother Tree: Uncovering the Wisdom and Intelligence of the Forest by Suzanne Simard

A Food Forest in your Garden by Alan Carter, Aberdeen-based forest gardener. Available direct from Permaculture Press.

The Wisdom Jesus by Cynchia Bourgeault is an excellent book on how the teachings have been distorted by Empire and how to discover the wisdom of the heart. We include this book as a key recommended reading in our Heart Of Living Yoga Teacher Training.

Swami Satchidananda (1977) Beyond Words. Integral Yoga Publications. PDF Accessed at https://lightinnerlight.com/wp-content/uploads/Beyond-Words-PDF.pdf 2nd October 2021.

A video tour of Rosa and James’s ‘impossible garden’ in Shetland. We’ve been very lucky to house sit for Rosa and James at Lea Gardens while searching for our own home.

The Impossible Garden (2004) by Rosa Steppanova describes how she and her partner James developed the most amazing forest garden in Shetland.

This essay originally appeared in Less: A Journal of Degrowth in Scotland